All losers in China Hong Kong name game

When is Hong Kong Hong Kong or not Hong Kong? When is Hong Kong China Hong Kong?

The questions surrounding the name game of Hong Kong sound increasingly confusing at a time when Hong Kong (or should it be China Hong Kong?) Chief Executive John Lee and his team members plan to travel around the globe to tell a good Hong Kong story. To put it on the record, government officials said they want to tell a Hong Kong story, not a China Hong Kong story.

On last Wednesday (11/1), Hong Kong’s culture chief congratulated actor Michelle Yeoh after she won a Golden Globe for her role in comedic adventure flick Everything Everywhere All at Once. Kevin Yeung, whose official title is Secretary for Culture, Sports and Tourism, described the Malaysian as a “Hong Kong actor.”

Yeung said in a statement: “Michelle Yeoh first made a name in the Hong Kong film sector, then moved on to the international stage with her exceptionally outstanding acting skills and hard work… We are really empowered by the fact that Hong Kong actors have continued to shine in the global film industry.”

Born in 1962 in what is now-Malaysia, Yeoh was once married to a Hongkonger. She rose to fame performing her stunts in Hong Kong movies such as Yes, Madam and Policy Story 3: Supercop before landing a role in the 1997 James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies. She went onto international stardom after starring in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, with Chow Yun-fat.

Yeung’s swift act of spinning the glory of the award-winning Malaysian to become another Hong Kong success story was greeted with scorn by netizens.

If his thick-skinned congratulatory note was aimed to promote the brand of Hong Kong, his statement on an order for all Hong Kong sports associations to include “China” in their official names or risk having funding cut could not be more hypocritical.

The Sports Federation and Olympic Committee of Hong Kong has earlier told its member associations to complete the name change by July 1.

Of the 83 Hong Kong sports associations listed on the Olympic Committee’s website, fewer than 20 have “China” in their names. They include the Hong Kong Football Association and Hong Kong Tennis Association.

Yeung threw his weight behind the Olympic Committee’s decision, but sidestepped a question of whether funding would be withdrawn if the sports associations failed to include “China Hong Kong” in their official names.

Under the Basic Law, the Hong Kong sports sector can participate in international sports events and activities under the name “Hong Kong, China”. It does not require the sports associations to include “China Hong Kong” in their official names.

The arrangement that helps preserve the Hong Kong identity of local sports associations while allowing them to compete as a team separate from the national team under “Hong Kong, China” has been a success.

It has demonstrated to the world, or the sports world at least, how the “one country, two systems” policy works.

The order by the Olympic Committee to have the sports association had their name changed is unnecessary. More damagingly, it may put pressure on other sectors to follow suit, creating trouble for numerous associations and organisations and confusion to the public.

If the rationale stands, the Hong Kong Jockey Club should be renamed as China Hong Kong Jockey Club, Radio Television Hong Kong Radio Television China Hong Kong and Hong Kong Police, China Hong Kong Police; Hong Kong Chief Executive, China Hong Kong Chief Executive.

It sounds ridiculous. But there are more signs that an overdose of the propagation of the principle of “one China” risks corroding the Hong Kong identity and damaging the Hong Kong brand.

That could not be more ironic as the Government hailed a recent ruling by the World Trade Organisation against a requirement by the United States authorities for all products imported from Hong Kong to be marked with a “Made in China,” instead of a “Made in Hong Kong” label.

If political correctness of upholding “one country” principle is to prevail, all Hong Kong exported products should perhaps be marked with a “Made in China Hong Kong” label. Why all the fight for a “Made in Hong Kong” label?

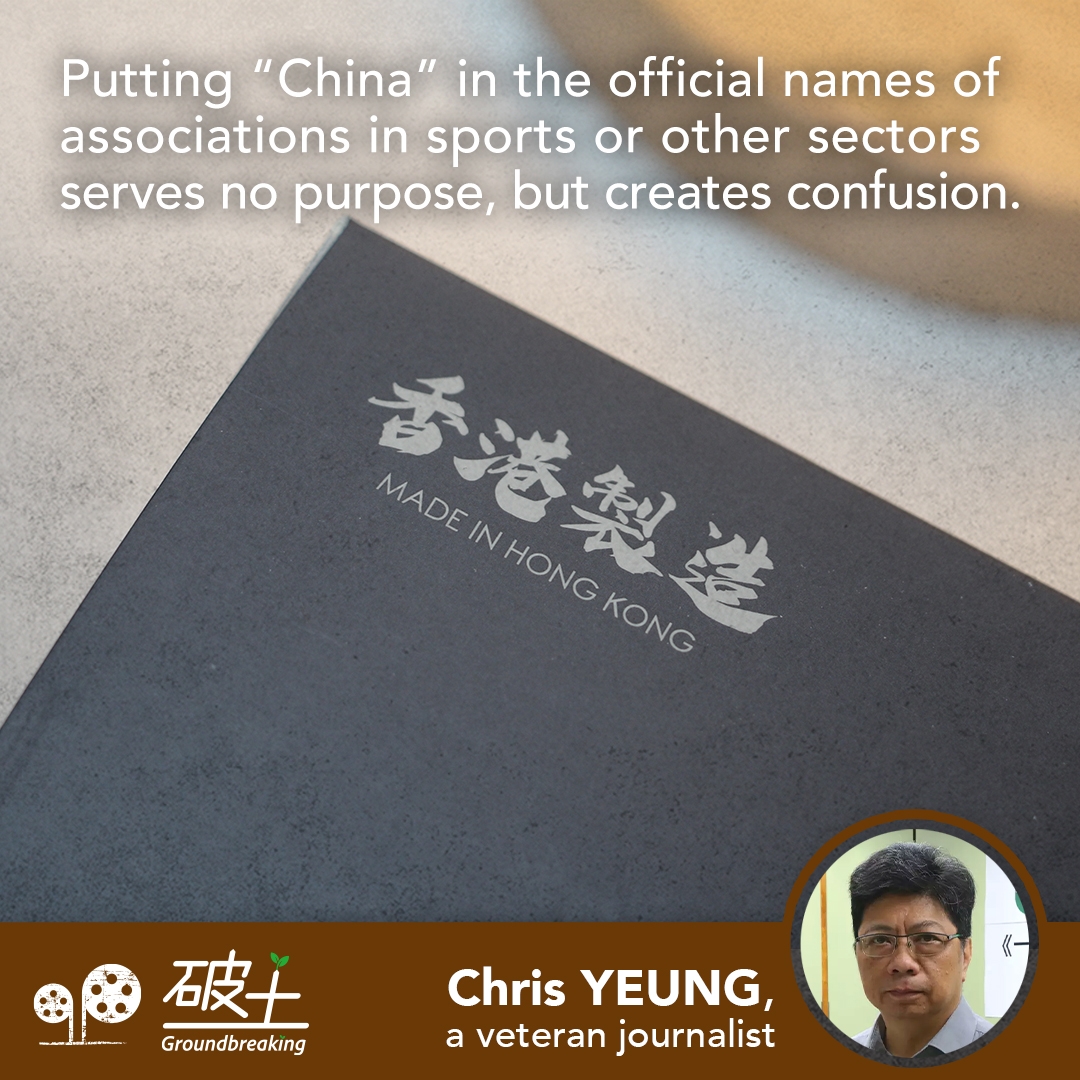

Hong Kong is never an independent state, both before and after 1997. Putting “China” in the official names of associations in sports or other sectors serves no purpose, but creates confusion.

Worse still, it risks causing unintended consequences of diminishing the much-valued Hong Kong identity, making the task of telling a Hong Kong story more difficult.