Where have Ombudsman’s reports gone?

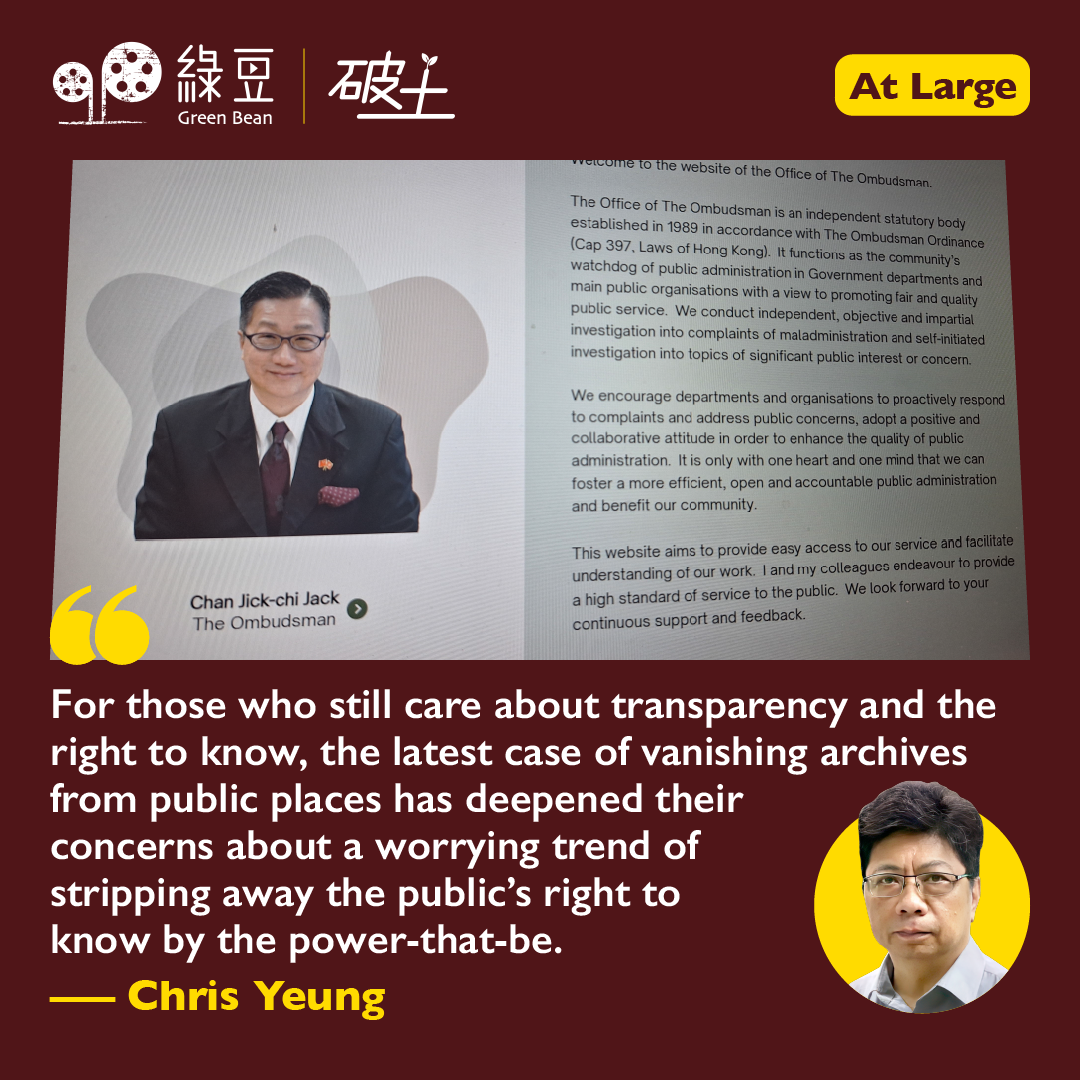

“This website aims to provide easy access to our service and facilitate understanding of our work. I and my colleagues endeavour to provide a high standard of service to the public.”

So said Jack Chan Jick-chi, head of the Ombudsman’s Office, in his welcome remarks on their official website.

Inaugurating a new section on Code on Access to Information on the website, his predecessor Lau Yin-hing wrote doing so was to help the public understand their right to have access to information held by government departments or public bodies – and for the departments and bodies to learn from the relevant public complaints against transparency.

Lau was hoping that the section would become a database as reference on the subject of access to information. She stood down in 2019. Chan took up the post in April 2024.

Missing Ombudsman’s reports

On Friday last week (16/5), the Chinese-language Ming Pao reported that they found the section on access to information, which contained details of cases of public complaints, disappeared from the website.

Gone are also investigation reports on government departments’ maladministration and press releases by the Office published before April, 2023. Only the annual reports published in 2022 and 2023 were available on the website. According to Ming Pao, at least 230 Ombudsman’s reports have been removed from the website.

In response to Ming Pao’s enquiry, the office said the website revamp was to ensure the content was accurate, effectively managed and updated. Members of the public, the office said, could write to them to ask for information not available on the website.

With the advent of technology and an ounce of skill in website design, keeping the records of past annual reports, investigations and public complaints relating to access to information does not sound an arduous task.

Making it easier and more convenient for the public to search for information by improving the website should no doubt be welcomed. But making it more difficult and inconvenient for the public to have access to the office’s information in the name of a website revamp makes a mockery of the mission of the Ombudsman’s Office.

Stripping away the public’s right to know

In a declaration on their website, the office has vowed to ensure Hong Kong is served by a fair and efficient public administration which is committed to accountability, openness and quality of service. Of a set of values listed, one reads “making ourselves accessible and accountable to the public and organisations under our jurisdiction.”

The removal of massive information from the office website, only to be available (perhaps) to the public after going through a maze of bureaucratic procedures, is a step backwards. The new arrangements are less open and accessible than before.

The “disappearance” of information from the Ombudsman’s official website but made available upon request may sound perplexing to ordinary citizens. Some may dismiss it as insignificant. Many may not be aware of it; they couldn’t care less.

But for those who still care about transparency and the right to know, the latest case of vanishing archives from public places has deepened their concerns about a worrying trend of stripping away the public’s right to know by the power-that-be.

The past few years saw the disappearance of sensitive programmes from the website of Radio Television Hong Kong, controversial books from public libraries, blurred identities of who said what at Legislative Council meetings. The list goes on.

Set a bad example

Under the existing Code of Access to Information, members of the public can apply for access to information from government departments and public bodies.

In 2018, a Law Reform Commission subcommittee has published a consultation document on whether the regime of public access of information held by the Government should be reformed and, if so, how.

Chairman of the subcommittee, Russell Coleman, SC, said they held the view that a law on information access should be enacted.

The consultation ended with no moves being taken by the Government to improve the regime of access to information, nor ways to enhance their openness and transparency.

The opposite seems to be true. The way the Government has operated, policy decisions formulated and decided has become more opaque. Pressure from lawmakers, media and civil society organisations for the Government to be more open, accountable and transparency has been lessening.

It could not be more ironic that the Ombudsman’s Office has moved to relocate their much-valued investigations and findings on maladministration, cases of complaints against information access to the corridors of bureaucracy.

By doing so, it has set a bad example of open and transparency governance, weakening its authority in beating maladministration.

▌ [At Large] About the Author

Chris Yeung is a veteran journalist, a founder and chief writer of the now-disbanded CitizenNews; he now runs a daily news commentary channel on Youtube. He had formerly worked with the South China Morning Post and the Hong Kong Economic Journal.