The UK’s Proposal to Amend the Extradition Act

About [De Bene Esse]

This Latin phrase can roughly be translated as “for what it’s worth”. In law, this phrase refers to proceedings taken to prevent future loss of evidence by the death or absence of a witness, or evidence admitted on a provisional basis without determining its admissibility. The evidence is allowed to stand for the present, subject to future challenges, by then it will stand or fall according to its intrinsic merit and admissibility. This phrase is borrowed here to suggest that the views expressed in this column are provisional, an alternative view for what they’re worth, subject to challenges or disagreement, for no one can claim a monopoly over truth, whereas rational debates and disagreement form the bedrock of a free society.

***************************************

The UK Government recently proposed amendments to the Extradition Act 2003 to allow “case-by-case” extradition arrangements with Hong Kong, sparking widespread concern among the Hong Kong community in the UK.

There was a formal extradition treaty between the UK and Hong Kong, but in 2020, the UK unilaterally suspended that treaty in response to the enactment of the Hong Kong National Security Law; the Hong Kong government immediately reciprocated, suspending the treaty’s operation. Since then, there has been no effective extradition mechanism between the two jurisdictions.

Under the current UK Extradition Act, extradition arrangements are divided into three categories:

- Part 1 covers European Union member states and is warrant-based.

- Part 2 covers territories with which the UK has a formal extradition arrangement, and is request-based; Hong Kong is listed under Category A of this Part.

- Section 194 of the Act allows the UK to enter into a “special extradition arrangement” with a country or territory without any existing formal extradition treaty or arrangement, that is, not designated under Part 1 or Part 2. This is a one-off arrangement for an individual and a specific case.

This “special arrangement” is distinct from treaty-based extradition: it is a discretionary scheme, meaning that the UK Government can simply refuse the request. If the UK government is prepared to consider the request, it will conclude a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the UK and the requesting territory, setting out the details of the arrangement. The extradition proceeding could only be invoked after the MoU is signed.

“De designate” Hong Kong

The legal problem is this: Part 2 of the Extradition Act is underpinned by the existence of an extradition treaty that is in force. Since the UK-Hong Kong treaty has been suspended since 2020, there is no legal basis for any extradition arrangement to be made under Part 2. At the same time, Section 194 cannot be invoked for any territory that is designated under Part 1 or Part 2. As a result, Hong Kong currently falls into a legal void: there is no functioning treaty basis for extradition under Part 2, and yet the one-off mechanism under Section 194 is not available, even if there were strong operational grounds for an extradition.

This is why the UK Government is proposing to amend the Act: it intends to “de-designate” Hong Kong—removing it from Part 2—thereby treating Hong Kong as a “non-treaty territory” and making it eligible for the Section 194 case-by-case framework. Technically, this is not a revival of the old extradition treaty; indeed, Hong Kong’s status would be downgraded from a “treaty partner” to a “non-treaty territory.” As the UK Government put it, this represents a “complete” severing of extradition ties, except that it is not a clean break because at present no extradition is legally possible at all, whereas after the amendment a one-off extradition arrangement could be made, presumably under exceptional circumstances.

Under the proposed mechanism, if the UK receives an extradition request from Hong Kong, the Home Secretary would decide whether to negotiate and sign a MoU providing for a special arrangement. Once that MoU is in place, the Home Secretary could certify the request and trigger the extradition proceedings, in which case the procedure in Part 2 of the Extradition Act will apply (subject to some modifications). Upon certification, the case will enter the UK judicial system. The extradition request will be considered by a UK court, which must determine whether the request meets the requirements of the UK law and any further conditions in the MoU.

Safeguards from the Act

The Extradition Act imposes several safeguards, including:

- The alleged offence must be an “extraditable offence” (which generally excludes “political offences”).

- There must be a prima facie case against the person sought, supported by sufficient admissible evidence.

- The speciality rule applies: the person can only be tried for the offences listed in the extradition request.

- The request must not be made for political or other improper purposes (“extraneous considerations”).

- Under certain situations, the UK consular officials must retain the right of access to the extradited individual and be able to monitor the progress of prosecution (“hostage-taking considerations”).

- Extradition must not violate the UK’s obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)—for example, the prohibition on torture or inhuman treatment, and the right to a fair trial, including the right to speedy trial and an access to legal counsel.

Disputes over whether an alleged offence is an “extraditable offence” or whether the extradition would violate the ECHR (as incorporated by the Human Rights Act 1998) are the most common issues in extradition cases. To qualify as an extraditable offence, the conduct must amount to a criminal offence in both jurisdictions (dual criminality). The requesting government must submit sufficient supporting documentations, including a statement of facts, evidence supporting a prima facie case, and relevant court decisions, if any.

Because “political offences” are typically excluded, extradition requests are often framed around more neutral offences—e.g. public order crimes like rioting, or serious criminal offences like money-laundering. However, in considering whether the offence is extraditable, the UK courts will look at the substance and not just the form of the offence.

They will examine the factual context leading to the offences and any other relevant circumstances to determine whether there are sufficient evidence to support the offence and whether the request is genuine or essentially political. The courts will also have to be satisfied that the extradition is a proportionate restriction on human rights, taking into consideration whether the extradited person will be able to receive a fair trial by an independent and impartial judicial authority.

For example, if the requesting country still carries out death penalty, this is a ground for refusal—though some countries that have retained death penalty may provide an assurance not to execute an extradited person if there is a guilty verdict. Whether such assurances are credible would factor into the Home Secretary’s decision to sign a MoU.

Unease among Hong Kongers in the UK

The current proposal also covers Chile and Zimbabwe. Both are currently listed under Part 2 alongside Hong Kong.

- Chile is in Category B of Part 2 (requiring higher evidential standards) but she has recently signed the European Convention on Extradition, accepting EU-style evidential rules. The UK is therefore shifting Chile to Category A of Part 2. This is a purely technical adjustment and is unlikely to be controversial.

- Zimbabwe had an extradition arrangement with the UK under the Commonwealth framework, but after leaving the Commonwealth, that treaty lapsed for Zimbabwe. Recently, Zimbabwe has made moves toward improving its human rights and the rule of law; the UK now proposes to remove Zimbabwe from Part 2 so that the discretionary extradition regime under section 194 can apply.

Thus, the changes for Chile and Zimbabwe are based on a change of circumstances. In contrast, in the case of Hong Kong, the original extradition treaty was suspended on the ground that certain provisions of the National Security Law were considered incompatible with the extradition treaty. Those provisions remain unchanged.

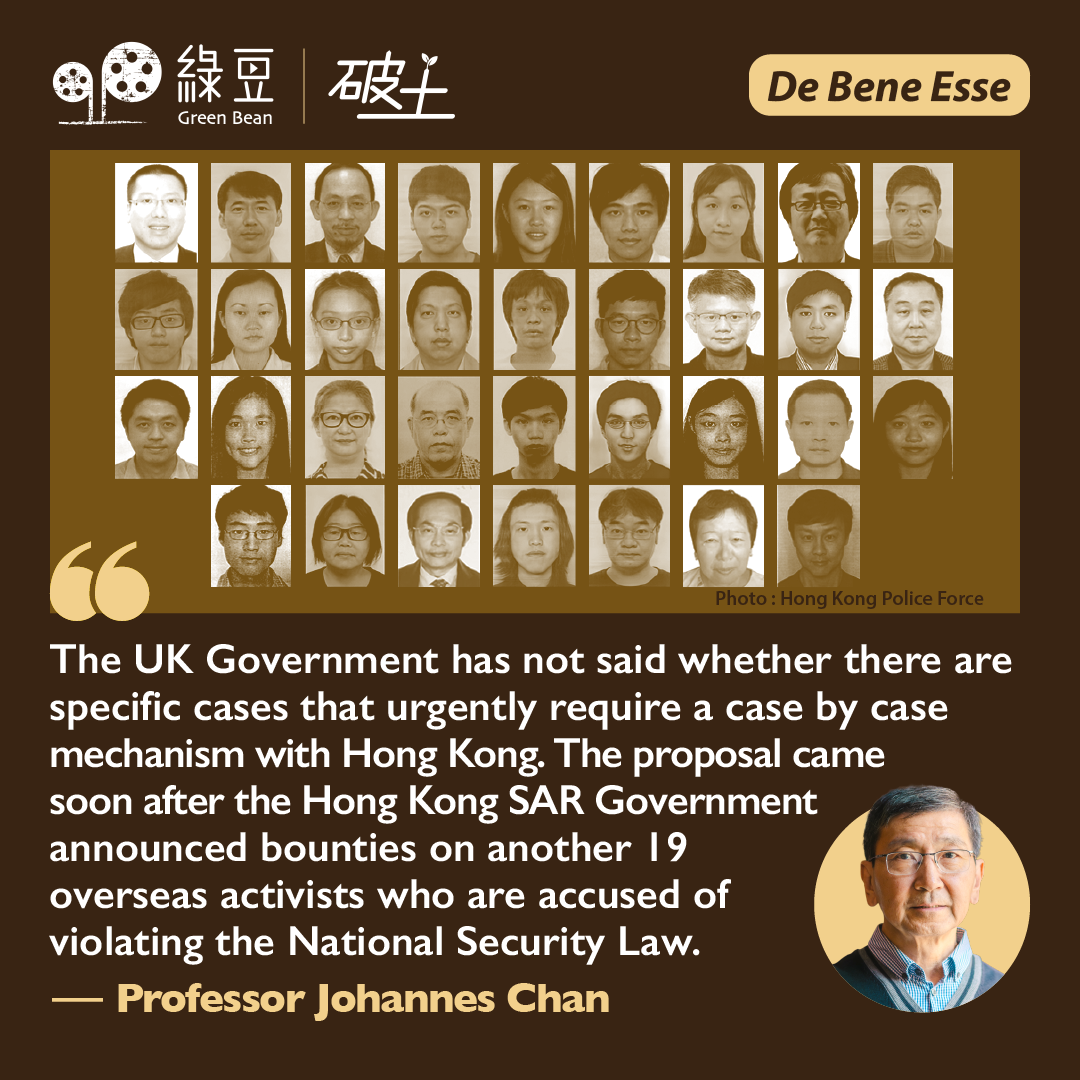

The UK Government has not said whether there are specific cases that urgently require a case-by-case mechanism with Hong Kong. The proposal came soon after the Hong Kong SAR Government announced bounties on another 19 overseas activists who are accused of violating the National Security Law, and around the same time as the new Labour Government proposed extending the residence period required for settlement in the UK. In contrast to the more permanent treaty arrangement in Part 1 and Part 2, a one-off MoU arrangement , due to its ad hoc and discretionary nature, offers less transparency.

Given the highly sensitive nature of the amendment and the timing of the proposal, it inevitably gives rise to suspicions as to what is motivating the proposed reform. Even with the built-in safeguards in the Extradition Act, this proposal has understandably caused considerable unease among Hong Kongers in the UK—particularly those who left Hong Kong for political reasons. The British Government will need to provide much stronger justifications to persuade Parliament and adequate assurances to allay the fear of Hong Kong people in the UK.

(Some parts of this article were published in Ming Pao, 30 July 2025)

▌ [De Bene Esse] About the Author

Professor Johannes Chan is an Honorary Professor of University College London and the former Chair of Public Law, The University of Hong Kong.