The relevance of military parade and hot-air balloon fiasco

Last Wednesday marked the climax of China’s latest show of power and drumming of nationalism by using a military parade in Beijing to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War.

In Hong Kong, local broadcasters gave live coverage of the parade as schools were told by the education authorities to reschedule classes for students to watch the live broadcast. Giant TV screens on some shopping malls dropped commercial ads for scenes at Tiananmen Square.

The news of the day drew mixed response from the populace, of whom many reacted with indifference and perplexity about the relevance of the commemoration to their daily life.

Prior to the September 3rd military parade, Chief Executive John Lee, his team and various government departments mounted a massive blitz of publicity on the war against the Japanese invasion with a focus on the role of guerrillas in Hong Kong and the neighbouring Guangdong province during the period.

It was aimed to promote nationalism and patriotism and an awareness of the paramount importance of upholding national security.

What does that mean to Hong Kong?

It is difficult to assess the impact of the intensive propaganda on the communist regime’s show of power and influence and boost for nationalism and patriotism among the Hong Kong populace, in particular the young generation. Time will tell.

Indicators such as social media and mass-oriented traditional media show the bitter victory of China 80 years ago did not seem to be a hot talking topic among the general public.

Many would probably agree with US President Donald Trump’s reaction to the parade that it was “very impressive.” But no more. So what. What does that mean to Hong Kong? Is it relevant? If so, how? Many people do not have an answer. Nor can they get some insightful – and honest – observations from news media reports.

Led by John Lee, Hong Kong had sent the largest-ever delegation to attend the parade. The delegation was composed of a total of 360 representatives, including senior officials, community leaders and students. There was no official announcement of the full list. Admittedly, ordinary people may not be interested to know.

But the dearth of transparency of who’s who in the Hong Kong delegation contrasts oddly with the enormity of importance the authorities have attached to the commemoration event. It does not help propagate the relevance of the commemoration of the historic event among the Hong Kong citizens.

Hot-air balloon Festival in Spotlight

It didn’t take long for the glitz of publicity of China’s mighty power and authority to fade out from the media.

One day after the parade, the headline stories of traditional media ranged from the verdict of a 2020 bomb plot, a government proposed regulatory framework for legalising ride-hailing services and a new police tactic against speeding.

The footage of a complaint by a mother against the organiser of a hot-air balloon festival for its failure to provide tethered rides at the Central Harbourfront ran viral on social media. The South China Morning Post ran a follow-up story of the balloon fiasco as the headline story on their Friday edition.

Shortly before the festival was kicked off on Wednesday, organisers announced they were not able to provide tethered rides after failing to get a license from the government. The government explained in a statement issued late Wednesday night they did so because of safety concerns.

The Consumer Council said it had received 28 complaints involving HK$40,118 as of 5pm Friday, with the largest amount at HK$4,956. The complaints were related to the lack of balloon rides.

The number of complaints and the amount of money involved were small compared to those relating to the Argentinian football star Lionel Messi’s “no-show” controversy last year, which drew more than 1400 complaints for his failure to join the friendly match with a Hong Kong team before the final whistle blew.

What draws the eyeballs of readers

That the hot-air balloon fiasco drew massive unwanted publicity in mainstream and social media as soon as the orchestrated military show ended raises a question of what draws the eyeballs of readers.

Citing the global Digital News Report 2025 compiled by the Reuters Institute in an article published in the Chinese-language Ming Pao on Thursday, Chinese University journalism professor Francis Lee Lap-fung said Hong Kong ranked third, followed Japan and Sweden, in a survey on avoidance of news among 48 countries and regions in the report. The higher the ranking shows the least avoidance of news among the people. In short, most Hongkongers do not avoid news.

35.9 percent of those respondents in Hong Kong who avoided news said they found the news content has nothing to do with them, followed by negative sentiments that may arise (29.5%)and distrust of news (8.8%).

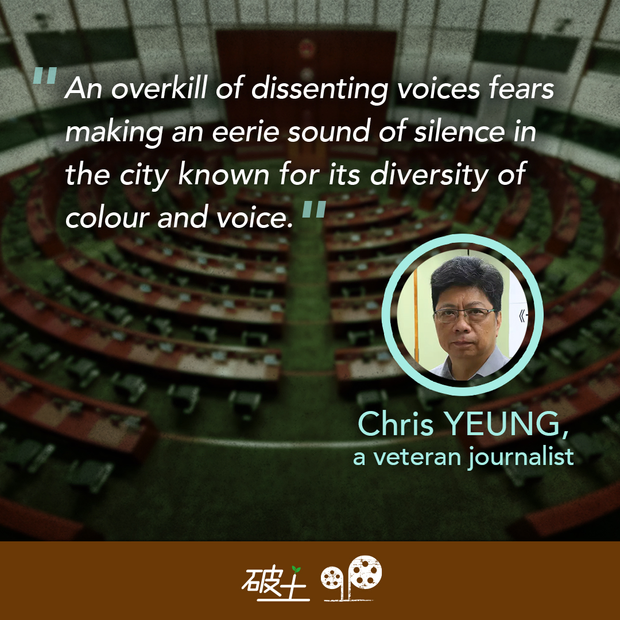

Lee attributed the feeling of irrelevance to the lack of voices of different opinions on social and political issues and government policies in recent years. Due to the change of social atmosphere, there were fewer people and organisations who were willing to give their views, he said.

“There are fewer news items that are able to draw public concern and feedback, making it difficult for ordinary citizens to feel news is relevant to them,” he said.

▌ [At Large] About the Author

Chris Yeung is a veteran journalist, a founder and chief writer of the now-disbanded CitizenNews; he now runs a daily news commentary channel on Youtube. He had formerly worked with the South China Morning Post and the Hong Kong Economic Journal.