Tai Po fire lays bare governance conundrum

With the exception of Donald Tsang Yam-kuen (2005-2012), Hong Kong’s three other former chief executives had plunged into governance crises ignited by mass protests during their reign. John Lee, whose five-year term enters its last 18 months on January 1, is faced with a different kind of crisis, which is, in a sense, even more damaging. The Tai Po fire took away at least 160 lives.

A look-back of the fate of the city’s chief executives made a sad read. Tung Chee-hwa, the first chief executive, was rocked by the July 1 protest in 2003 that saw half a million people take to the streets. He stepped down in 2005, citing sore legs. Leung Chun-ying survived the 79-day Occupy Central movement in 2014. He decided not to seek re-election in 2017, citing family reasons. Carrie Lam, Leung’s successor, was confronted with the worst political turmoil since the 1967 Riot, which was ignited by an extradition bill. She became another “one-term” chief executive at the end of her five-year term in 2022.

Then came John Lee, whose five-year term looks set to be marred by the deadly Tai Po Wang Fuk Court fire that caused at least 160 deaths and thousands of families homeless.

“Why you deserve to keep your job?”

Police and ICAC made swift arrests of people involved with the renovation work of the residential towers. Police and fire services’ initial investigations cited substandard scaffold nets, malfunctioned fire alarms as causes of the horrific fire or the worsening of it. Alleged long-running corruption in the tendering system in the construction industry has been blamed as an underlying cause of safety risks at construction and renovation sites. Rightly or wrongly, critics say regulatory and supervisory failures of multiple government departments, including the Labour Department, Housing Department, Buildings Department, are part of the “man-made disaster.”

As the city’s “person responsible” for Hong Kong, Lee has not been targeted. There have been no calls for his resignation to show accountability for the calamities under his administration.

In an attempt to raise the sensitive question of resignation, an AFP reporter asked him at a press conference last week, “Over the past few years, you have spoken about leading Hong Kong from chaos to order and from order to prosperity. And yet this prosperous society allowed 151 people to burn to death. Can you tell us why you deserve to keep your job?”

Lee sidestepped the question. He said: “Yes, it is a tragedy; it is a big fire. Yes, we need a reform. Yes, we have identified failures in different stages. That is exactly why we must act seriously to ensure that all these loopholes are plugged so that those who are responsible will be accountable, the shortcomings will be addressed, the bottlenecks will be addressed, and we will reform the whole building renovation system to ensure that such things will not happen again.”

“The Buck Stops Here”

Late US President Harry Truman had a sign on his White House desk that said on one side, “The Buck Stops Here”, meaning the President has to make the decisions and accept the ultimate responsibility for those decisions.

Writing on the Chief Executive’s blog on October 28 in 2016, Leung Chun-ying said the phrase “The Buck Stops Here” was also applicable in Hong Kong. “It’s easy to be a good guy. It takes commitment and courage to be a bad guy.” The Chief Executive cannot avoid making decisions that are controversial, or may offend people, he wrote.

It is too early to tell whether those who were found to have passed the guy in the bureaucracy that caused in one way or another the tragic fire would be held accountable after the judge-led committee concludes its findings.

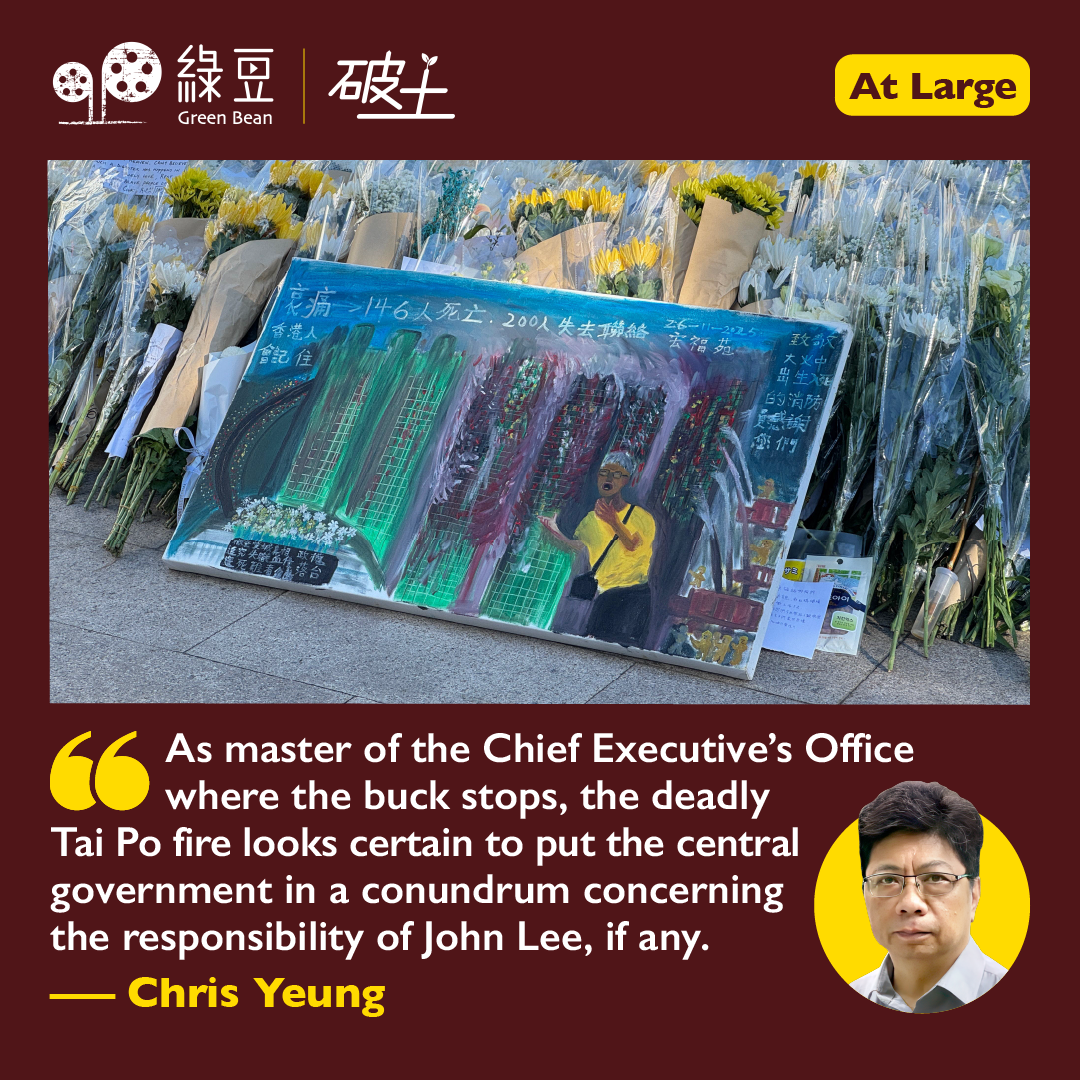

As master of the Chief Executive’s Office where the buck stops, the deadly Tai Po fire looks certain to put the central government in a conundrum concerning the responsibility of John Lee, if any.

Intriguingly, President Xi Jinping issued a directive hours after the blaze out ordering the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office and the Liaison Office in Hong Kong to provide assistance to the Hong Kong SAR government. Media reports said a fleet of fire-fighting vehicles stood by at the border for emergency orders for coming to the aid.

Three days after the fire, a State Council committee issued a nationwide order for immediate inspection of scaffold nets and safety of renovation sites. It did not name the Tai Po fire.

Based on the definition laid down by the State Council, the Tai Po calamities could fall into the category of “major work safety accident” that the relevant local government officials may have to be held accountable. The State Council directive does not directly apply to Hong Kong. But it doesn’t sound irrelevant to the city’s governance both in work safety and as a whole.

Dilemma faced by the central government

An article published in The Diplomat, an international current-affairs online magazine, gave a damning verdict on Hong Kong’s governance laid bare in the Tai Po fire. Its headline read, “No, Hong Kong’s governance is not becoming like China’s. It’s actually worse.”

The author, Owen Au, cited two work safety accidents in the mainland as cases in point.

Case One: “In 2010, following a residential tower fire in Shanghai that killed 58 people, Beijing immediately dispatched a State Council investigation team. Subsequently, 26 people, including government officials, were charged with criminal offenses, and the Communist Party disciplined 28 others. On top of that, Shanghai’s mayor at the time publicly apologized.”

Case Two: “… after the 2021 Henan floods, which caused nearly 400 deaths, the State Council released a detailed report outlining institutional failures. The report resulted in eight criminal prosecutions and disciplinary measures against 89 officials, including several mayors and deputy mayors.”

Enter the Tai Po case. One day after it broke out, the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office under the Communist Party dispatched a working team led by two senior officials to Hong Kong to provide assistance. Official reports did not give details of the scope of work of the work team.

On Friday, Lee named a three-member team led by High Court judge David Lam to investigate the fire, adding it would be given “reserve power” to invoke powers provided in the Commission of Independent Inquiry ordinance for the committee upon their request.

It is anybody’s guess whether the State Council has or will conduct its own report on the fire, like other “major accidents” in the mainland.

In The Diplomat article, it highlights a dilemma facing the central government in view of the “one country, two systems” constitutional framework.

It says, “Acknowledging serious failures by the city’s government would undermine the rationale for its post-2019 political restructuring.” “Moreover, the principle of ‘Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong’ restricts the ability to draw replacements from the broader mainland bureaucracy.”

The chance of a replacement by another Hongkonger could come on 30 June 2027 when Lee’s term expires – if Beijing thinks so.

▌ [At Large] About the Author

Chris Yeung is a veteran journalist, a founder and chief writer of the now-disbanded CitizenNews; he now runs a daily news commentary channel on Youtube. He had formerly worked with the South China Morning Post and the Hong Kong Economic Journal.