HK journalists hit by bad news

Hong Kong journalists have found themselves the subject of bad news following the restart of the legislative process of Basic Law Article 23 last week.

First, the Government has proposed defining state secrets along the nation’s state secret legislation, widening the scope of secrets relating not just to defence and foreign relations matters, but China’s socio economic and technological development.

Secondly, a public interest defence against the proposed offence of disclosing state secrets was not included in the latest government proposals.

Public interest defence

Back in 2002, the then Tung Chee-hwa administration had added a clause of public interest defence in the revised bill on Article 23 in an eleventh hour of the legislative process. Amid massive public opposition against the bill, the revision was aimed to ease public discontent in the hope of winning its approval at the Legislative Council. It was proved to be too little, too late. The rest is history.

Adding public interest defence is vitally important to the media for them to defend themselves if they are taken to court for publishing materials that the Government insisted as state secrets. Citing the clause, journalists could argue the disclosure serves public interest. It is important to note that it is a clause for defence, not for exemption.

Its omission from the government proposals was immediately picked up by Executive Council Convenor and legislator Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee at a government briefing session on the proposals at the Legislative Council after they were released for public consultation.

Ip asked officials whether they would consider adopting a clause of public interest defence, similar to the UK law, in light of Hong Kong’s status as an international financial centre.

Bar Association chairman Victor Dawes has further suggested that anyone arrested for state secrets offences under the proposed national security legislation should be entitled to a public interest defence but stressed the threshold “cannot be low”.

High threshold

Both Secretary for Justice Paul Lam and Secretary for Security Chris Tang have reacted cautiously to the proposed inclusion of the clause, but stressed that a “high” threshold is needed.

Lam told NowTV last Friday that there could be “extreme”, “exceptional” circumstances in which the public interest would come before the protection of state secrets, such as when people’s lives were at stake.

He hinted that even if a public interest defence clause is added into the law, the threshold for disclosure “must be very high.”

Judging from the officials’ quick response, it looks likely that the Government will adopt the defence clause ultimately but with a high threshold for disclosure.

By doing so, the Government may claim they are receptive to public opinion. But a defence clause with a high threshold means almost nothing to journalists for them to defend themselves when facing charges of leaking state secrets.

Elements of “abetting”

If the likely inclusion of a public interest defence clause with high constraints fails to brighten the mood of the press, the blitz of remarks given by the two-men Article 23 propaganda team has added more gloom to journalists.

Speaking at the same NowTV interview, Lam urged the media to be more “cautious” and consider whether elements of “abetting” are involved when interviewing wanted Hong Kong activists.

He explained doing those interviews may amount to giving them a platform to express views in breach of national security.

Speaking on the same Cantonese TV programme, Chris Tang said that whether the media would risk breaking the law by interviewing wanted activists would depend on “different circumstances.”

He said: “Interviewing someone is simply conducting an interview. However, if there is an appeal for others to donate money to them after the interview, could that be considered as assisting these fugitives? It depends on the specific context and circumstances,” he said in Cantonese.

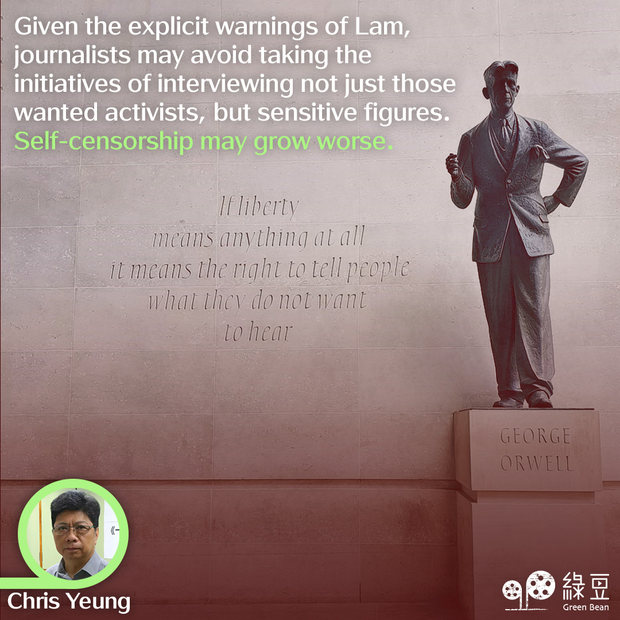

Self-censorship

Last year, the Government placed a HK$1 million bounty each on 13 activities who left the city. They include ex-lawmakers Ted Hui and Dennis Kwok, Nathan Law and Kevin Yam.

Lam’s warning has deepened the prevailing fears among journalists about the risk of breaching the national security law if they conducted and published interviews of wanted activists even though the content of the stories did not constitute a breach of any laws.

This is because journalists will not be able to rule out the possibility that their interviews with wanted activists could be used by anyone to raise funds for the activists.

Given the explicit warnings of Lam, journalists may avoid taking the initiatives of interviewing not just those wanted activists, but sensitive figures. Self-censorship may grow worse.

The more the “red lines” the less freedom of the press journalists and fellow citizens have been promised.

▌[At Large] About the Author

Chris Yeung is a veteran journalist, a founder and chief writer of the now-disbanded CitizenNews; he now runs a daily news commentary channel on Youtube. He had formerly worked with the South China Morning Post and the Hong Kong Economic Journal.