Departure of UK judges dims top court

Flashed back to 2021, Jonathan Sumption, a retired British judge who sat on Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal (CFA) as a non-permanent overseas judge, said no to calls for him to resign from the city’s final appellate court.

He defended the city’s judicial independence, insisting he intended to continue serving the CFA and would not bow to demands by British lawyers for Western judges to resign.

He had said the “permanent judiciary of Hong Kong is completely committed to judicial independence and the rule of law”, and the “Chinese and Hong Kong governments have so far done nothing to interfere with the independence of the judiciary”.

Sumption, like other overseas judges of the CFA, felt the heat following the resignation of two non-permanent judges – veteran Australian justice James Spigelman and former top British judge Baroness Brenda Hale – following the enactment of the Beijing-decreed national security law in 2020.

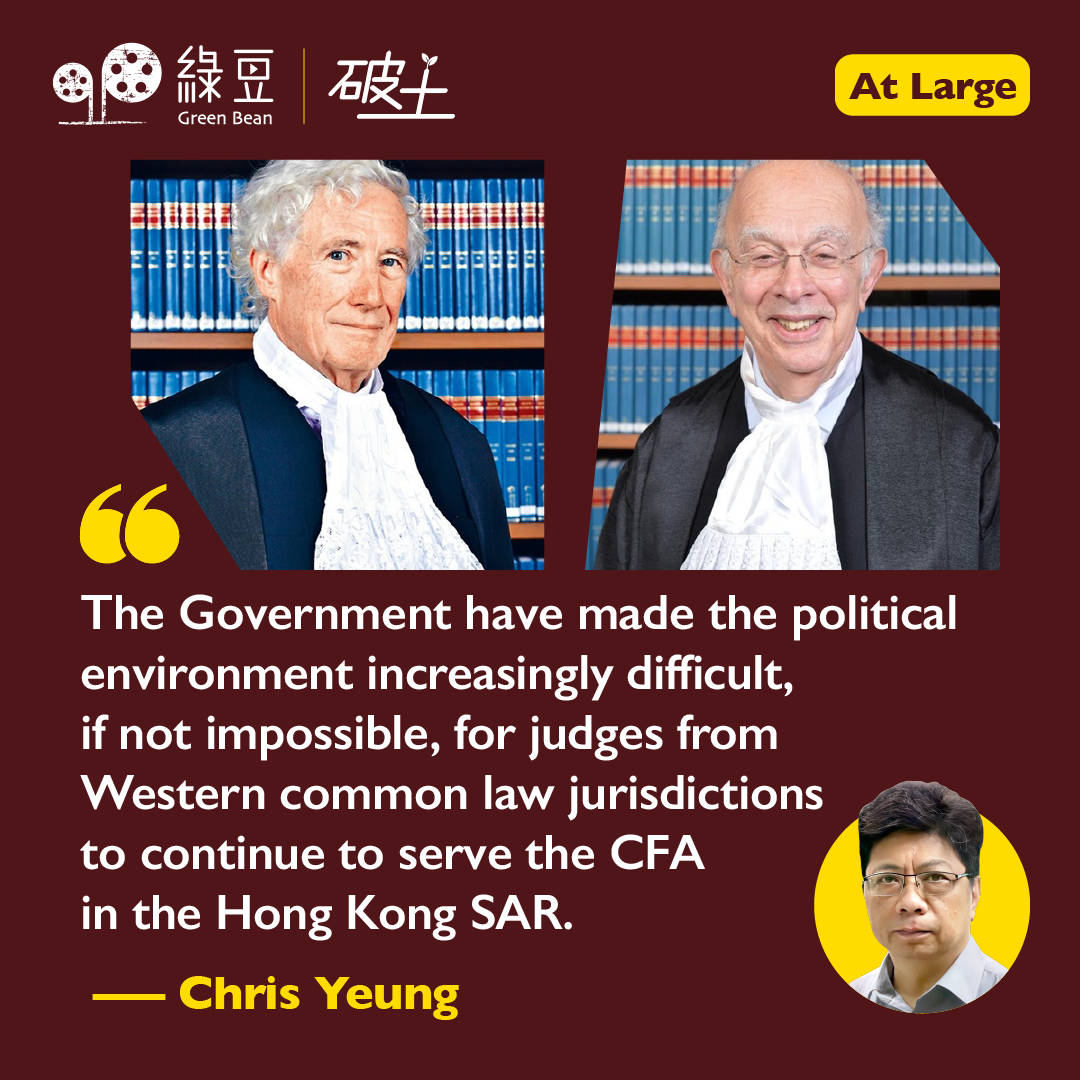

In 2022, British Supreme Court president Lord Robert Reed and vice-president Lord Patrick Hodge resigned from the CFA.

Last week, Sumption and another British judge Lawrence Collin confirmed their resignation from the CFA. Collins said in a statement: “I have resigned … because of the political situation in Hong Kong, but I continue to have the fullest confidence in the court and the total independence of its members.”

Sumption said he will make a statement next week.

Political environment

It remains unclear what Sumption will say about his aboutturn. But top advisers and unidentified officials in the Hong Kong government have already drawn their conclusion. They fingered at the UK government and parliamentarians for putting pressure on the judges.

There may be some truth in their accusation given the fact that there have been calls from British politicians for overseas judges to resign from the CFA since the enactment of the Hong Kong national security law.

But instead of blaming those who put pressure on the British judges, it will be more realistic for the Government and its allies to ask what they could do to deflate the political pressure on them.

Events that unfolded since the NSL took effect in July 2020, however, have done the opposite. They have made the political environment increasingly difficult, if not impossible, for judges from Western common law jurisdictions to continue to serve the CFA in the Hong Kong SAR.

The Government came under strong criticism for the erosion of civil liberties by Western governments and human rights groups. The revamp of the electoral system has been slammed as a rollback of democracy.

Despite its strong denials, the Government has achieved little in moderating the sharp conflicts with Western governments on the city’s human rights record.

Long shadow

The past two weeks saw Hong Kong the subject of bad publicity in international media.

For the third year in a row, there were no candle-light vigils held at Victoria Park on the evening of June 4 to commemorate the victims of the Tiananmen Square crackdown. Days before the June 4 commemoration, three national security judges found 14 of 16 pro-democracy activists, who were charged with subversion for joining a Legislative Council primary in July 2021, guilty. The other 31 defendants in the case have earlier pleaded guilty.

Although the judgment of the Legco primaries case is long, it should not come as a surprise that Western democracy will find the argument of the conviction of the pro-democracy activists for subversion on grounds of threatening to indiscriminately vote against the Government’s Budget thin and weak.

To critics and cynics, it is a political trial that has raised serious questions about Hong Kong’s rule of law, common law system and independent judiciary, like it or not.

Revelation that an office manager of Hong Kong’s Economic and Trade Office in London was accused of spying has fuelled fears in the UK about the alleged increased work of China’s overseas intelligence network.

With no sign of an easing of crackdown on what the authorities deemed as threats to national security, the city’s political environment looks set to become more difficult for judges from Western democracies.

By giving a greenlight to the setting up of a panel of non-permanent overseas judges to sit on the CFA in a bill that passed into law before 1997, Beijing had put pragmatism above nationalism. It had helped salvage confidence shattered in the aftermath of the June 4 crackdown.

Three decades on, the departure of overseas CFA judges one after another since 2021 has cast a long shadow over the city’s rule of law, common law system and independent judiciary.