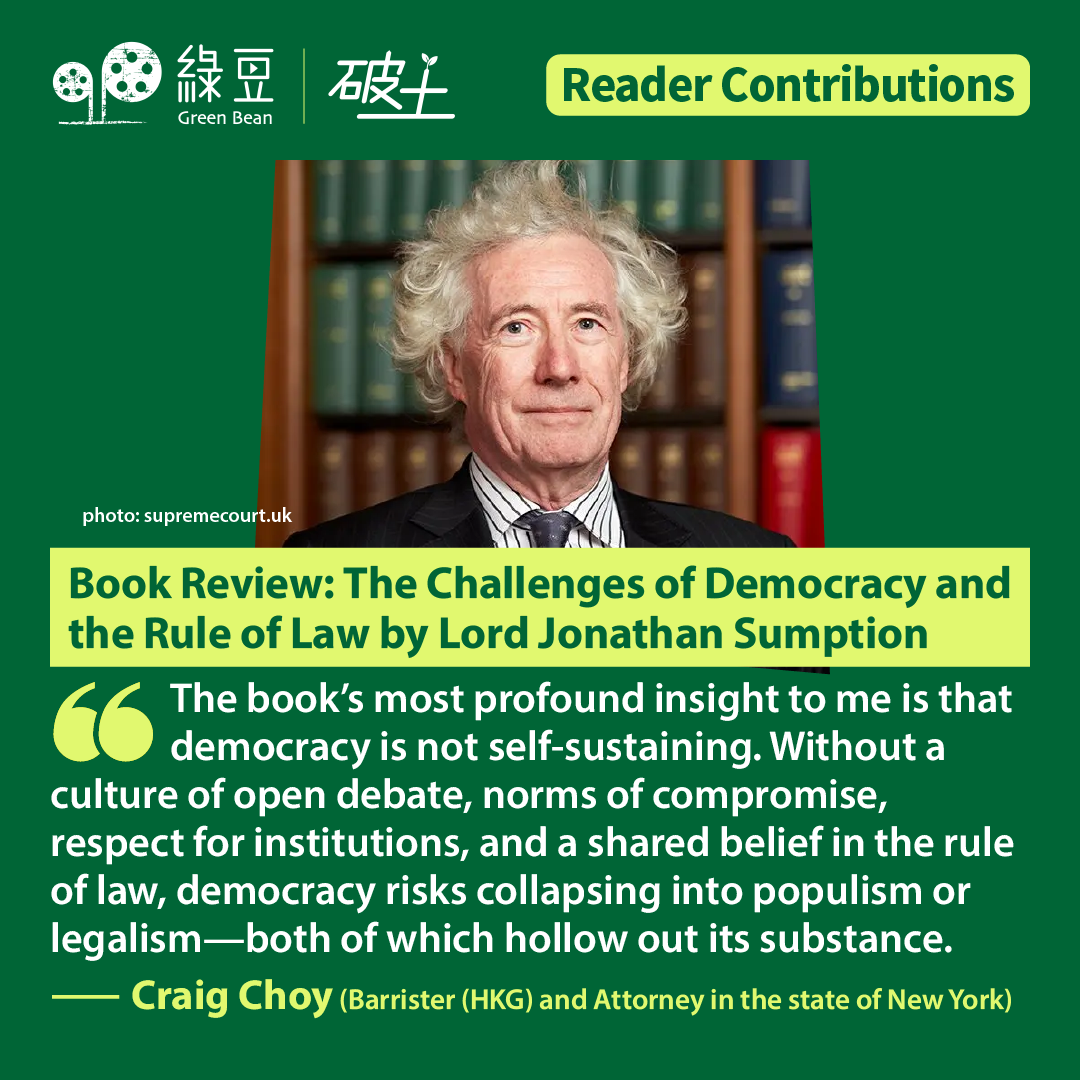

Book Review: The Challenges of Democracy and the Rule of Law by Lord Jonathan Sumption | By Craig Choy, Hong Kong Barrister and Attorney in the state of New York

(Editor’s Note: In addition to having regular columnists, We welcome opinions from readers across the political spectrum—Left, Centrist, and Right.)

After reading the classic The Rule of Law by Lord Bingham, I came across this new book by Lord Jonathan Sumption, a former UK Supreme Court Justice and distinguished historian, The Challenges of Democracy and the Rule of Law. In this book, Sumption delivers a clear warning to modern democracies: they are not failing because of external threats such as invasion or war, but because of decay from within—particularly a lack of compassion toward minorities. Sumption’s new book provokes a timely and vital conversation first illuminated in Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville: the danger of the “tyranny of the majority.”

Tyranny of the Majority Revisited

“The tyranny of the majority… is a danger inherent in democratic governments, and it may be said to be the dominant evil peculiar to them.”

— Alexis de Tocqueville

Sumption channels Tocqueville’s fear that, in mass democracies, majorities may come to dominate not only institutions, but also the moral and cultural life of society. He argues that democracy must not be reduced to the mere arithmetic of elections. Without constitutional limits, a culture of restraint, and institutional pluralism, even well-intentioned democratic forces can become oppressive.

This concern is not abstract. When populist governments use their mandates to suppress dissent, bypass deliberation, or undermine independent institutions, they invoke the language of democracy superficially while eroding its very foundations.

Thin vs. Thick Definitions of the Rule of Law

Sumption’s diagnosis of the decay of modern democracy led me to reflect on why it is important to adopt the thick definition of the rule of law in our system. A thick rule of law integrates substantive values, such as natural justice and human rights, into legal interpretation—ensuring the law serves the public good. In contrast, a thin definition, preferred by many authoritarian regimes, emphasizes mere adherence to procedures and institutional authority, which can result in the erosion of individual rights.

Rule of Law with Empathy

Building on Sumption’s thesis, I would argue that democracy and the rule of law only function when guided by a spirit of civic empathy—an ethos he hints at but does not formally endorse. Sumption’s emphasis on minimal judicial intervention and civic restraint implicitly demand that the majority voluntarily uphold minority rights. He argues that democracy survives only when the majority exercises a kind of civic compassion—respecting minority rights not because courts demand it, but because shared decency requires it. This, in essence, is what empathy is about. In this context, empathy becomes not just a personal virtue, but a constitutional compass—essential to governing inclusively and preserving legitimacy.

That said, an overly expansive interpretation of the thick rule of law—when wielded unchecked by the judiciary— can be problematic. Courts may end up imposing political morality under the guise of law, stepping beyond their proper constitutional role. This might lead well-intentioned policies, such as DEI initiatives, to produce unintended or even adverse consequences.

DEI: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

While Sumption doesn’t address DEI in his book, his framework inspired me to reimagine how such initiatives might be grounded in legal pluralism rather than moral mandates. DEI initiatives are often seen as tools to correct systemic imbalances in representation and participation. They can complement democratic systems by preventing the tyranny of the majority and addressing blind spots that elections alone cannot resolve.

However, DEI itself can fall into similar moral overreach if not properly grounded. To prevent that, DEI should be embedded within a structured, pluralistic conception of the thick rule of law—one that protects both group rights and individual freedoms and ensures that diversity and inclusion does not come at the cost of fairness.

Conclusion: Democracy Is Not Just About Process, But Culture

Lastly, the book’s most profound insight to me is that democracy is not self-sustaining. Without a culture of open debate, norms of compromise, respect for institutions, and a shared belief in the rule of law, democracy risks collapsing into populism or legalism—both of which hollow out its substance.

Sumption reminds us to remain vigilant—challenging both technocrats who fetishize law and demagogues who weaponize the people. Democracy is not rule by experts or masses, but by its culture and values, which are shaped and safeguarded by all of us under a shared civic life. And, empathy is the cornerstone of a successful and healthy democratic society.

Bonus: Hong Kong

In Chapter 4, Sumption references Hong Kong as a case study in the correlation between legal protections, democracy, and human rights. Once a high-trust, rules-based international financial hub, Hong Kong has experienced curtailment of judicial independence, politicisation of dissent and erosion of civil liberties. These changes, ushered in under the National Security Law, reveal precisely what Sumption warns against: when legal mechanisms are overridden by authoritarian majorities or political agendas, law becomes a façade—not a safeguard.