A new cold spell hits Hong Kong

Flashed back to July 1, 2020 when the Hong Kong national security law took effect, cartoonist Zunzi, veteran columnist Tim Hamlett and late patriot-democrat Szeto Wah had seemed to be the unlikely victims of the looming battle against subversives.

Government officials have assured, then and now, the law only targeted a “very small number of people.”

In a city with a total population of 7.4 million people, the numbers of people arrested and taken to courts respectively under the law so far are small. But the ramifications of major NSL cases that involved Jimmy Lai, founder of the Apple Daily, and the newspaper’s top editors and the seditious publication case of Stand News editors are profound and immense. The trials and their subsequent rulings have and will shake the media landscape.

The arrests of key editorial executives of the two media outlets, followed by the closure of another online platform Citizen News, had sent more chilly winds to the journalists’ circle. Following the fall of independent media outlets one after another in the second half of 2021 and early 2022, the mood of journalists fell to a nadir.

Since then, it has been a case of “no news is good news” with no new arrests of journalists and closures of media platforms. With hindsight, it is a case of “a lull before a storm”, albeit a less severe one compared with the Apple Daily case.

A spate of news that involved Zunzi, Tim Hamlett and Szeto Wah is bad news for the media and creative sector and society as a whole.

A Zunzi cartoon published on Ming Pao that ridiculed the power of appointment by the chief executive of district figures had emerged as the last straw on the back of the camel. Shortly after home affairs minister Alice Mak issued a strongly-worded statement condemning Zunzi, Ming Pao put an end to his cartoon columns beginning from May 14, without giving an explanation.

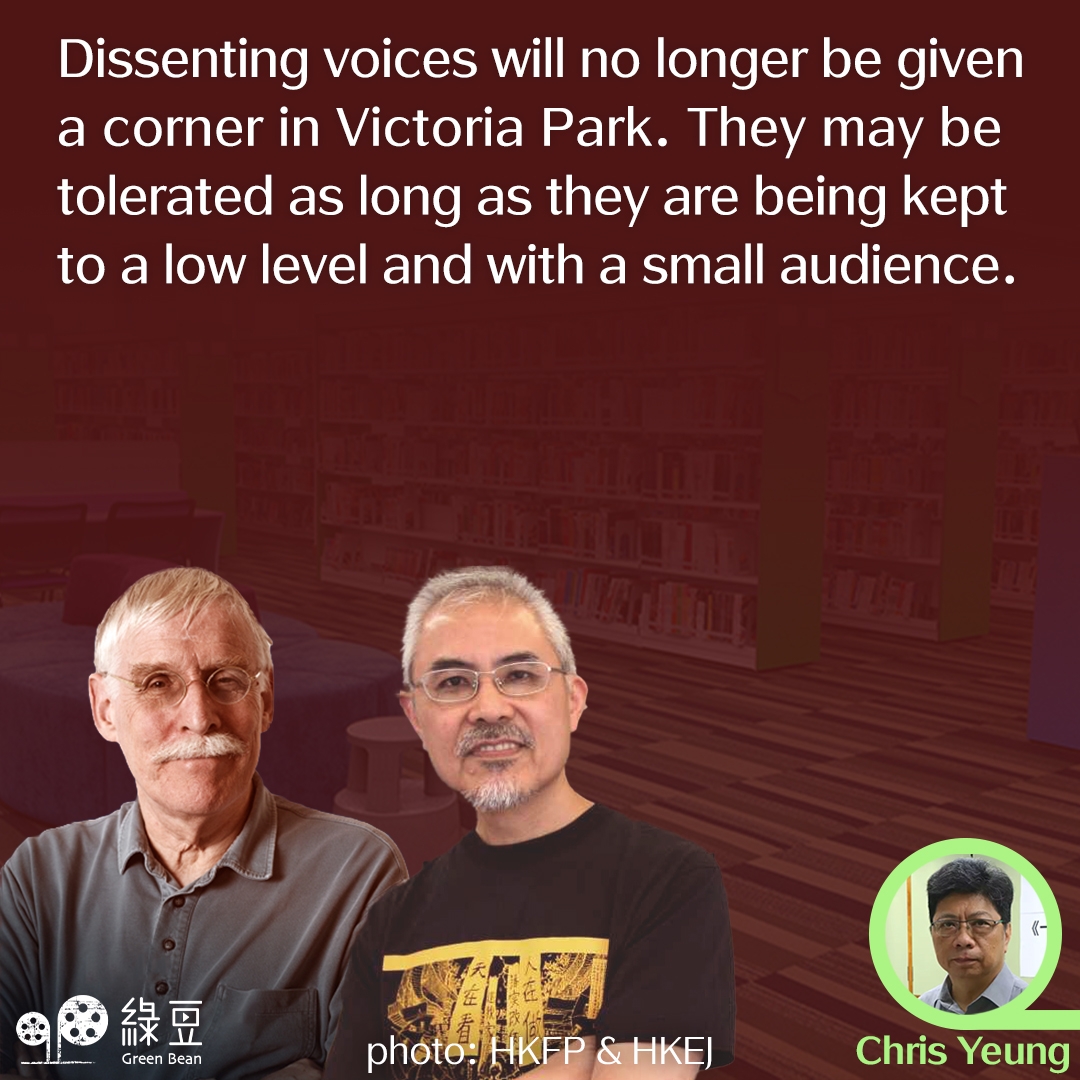

In the midst of the public outcry over the axing of Zunzi’s political cartoons, Tim Hamlett wrote in his column on an English online news platform, Hong Kong Free Press, on May 12 there will be “no more politics” in his columns.

He wrote: “There is no longer any point in writing about local politics… Also, the risks seem to be increasing… I do not aspire to be the last one. I am still up for new experiences but the inside of a Hong Kong police cell is not on my bucket list.”

Adding to the feeling of doom and gloom are revelations by various media organisations last week that more publications and videos that involved “political figures” have been taken down from the government libraries without an explanation.

They include The Great River Flows East, the memoir of Szeto Wah, travel books written by ex-journalist Allan Au and a book written by former legislator Margaret Ng Ngoi-yee about the female characters in the Kung Fu novels penned by Louis Cha, who wrote under his pen name Kam Yung.

Throwing his weight behind the government’s librarians, Chief Executive John Lee said on Tuesday material circulated by public libraries had to “serve the interest” of society without breaching the law. He did not define what constitutes “the interest of society.”

Zunzi and the list of authors whose books were made disappear from public libraries had not been arrested for alleged violations of laws, not to mention prosecution. Under the common law system, they are innocent until proven guilty. Their cartoons and books, however, have been given a verdict by John Lee, namely “not in the interest of the society.”

They were given the penalty of a de facto ban of their books in public libraries.

In the case of Tim Hamlett, it is a case of an “opt-out” on his own from the minefield of political writings against the background of an enduring hostile climate for journalists and people who are being seen as “them” by those in power.

That bad news came one after another may appear to be coincidental. It is not. With hindsight, the conclusion of the landmark 20th national congress of the Chinese Communist Party in October last year marked the beginning of a new round of initiatives to boost governance in the Hong Kong SAR.

It was about the same time that Zunzi’s cartoons published on Ming Pao had been singled out for bashing in statements issued by various policy bureaus and departments.

On the political front, the Government started putting the final touches on a revamp of district administration that featured a drastic cut of directly-elected seats in district councils. It was unveiled this month.

At the national level, the office on Hong Kong affairs has been put directly under the ruling party in a significant restructuring after the party congress aimed to strengthen Beijing’s control over Hong Kong policies.

If the district council election overhaul is aimed to oust/marginalise democrats in the low-tier political structure, the case of Zunzi, the book removal and Hamlett’s termination of political columns have one thing in common. When it comes to the fallout, they are part of the trend of marginalisation of dissenting voices in the media and public scene.

Books such as Szeto’s memoir and Zunzi’s cartoons have not been totally banned on Hong Kong soil. It may still be okay for Hamlett to write about arts and livelihood issues until it is not okay.

Dissenting voices will no longer be given a corner in Victoria Park. They may be tolerated as long as they are being kept to a low level and with a small audience. All in the name of “the interest of Hong Kong.”

▌[At Large] About the Author

Chris Yeung is a veteran journalist, a founder and chief writer of the now-disbanded CitizenNews; he now runs a daily news commentary channel on Youtube. He had formerly worked with the South China Morning Post and the Hong Kong Economic Journal.