A 1982 decolonisation plot crushed, finally

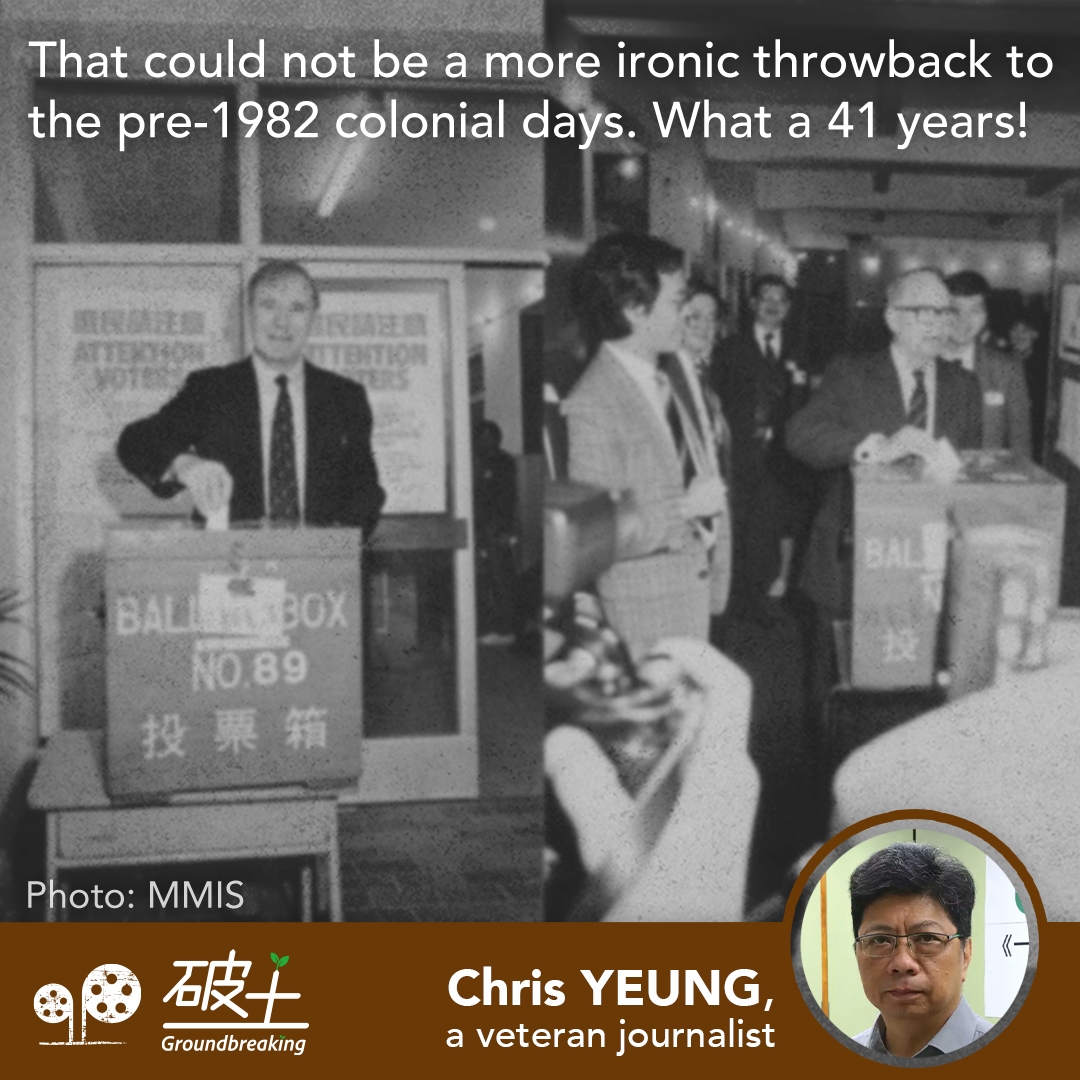

History is full of irony. The story of the setting up of district boards as one of the first major steps of decolonisation of Hong Kong in the 1980s – and their imminent overhaul by the Hong Kong SAR government four decades later could not be more ironical.

If the introduction of democratic elections at the district bodies in 1982 aimed to survive the sovereignty changeover as part of the British legacy, a government proposed plan to drastically thin out democracy in the revamped district councils will mark the end of the history of the British-style district administration.

Welcome to the SAR’s district administration system with Chinese, if not communist, characteristics.

Government officials maintained the revamp is an attempt to reshape the district councils in accordance with what it is supposed to be under Article 97 of the Basic Law, the city’s constitution promulgated in 1990 that became effective on July 1, 1997.

Referring to district boards (renamed as district councils after 1997), Article 97 says “district organisations which are not organs of political power may be established in the Hong Kong SAR to be consulted by the government on district administration and other affairs, or to be responsible for providing services in such fields as culture, recreation and environmental sanitation.”

Article 98 says the powers and functions of the district organisations and the method for their formation shall be prescribed by law.

Article 97 and Article 98 are the only two provisions under the section on district organisations in Basic Law’s Chapter IV that deals with political structure.

They are markedly brief and broad, giving ample room for flexibility in giving a bigger role for them for boosting public participation in district and community affairs and, at a different level, the city’s democratic development.

Even before the Basic Law took effect, the then district boards had already played a political role. They were consulted on major decisions and policies made by the British Hong Kong administration. They include the Sino-British Joint Declaration.

Though being explicitly branded as a British decolonisation plot before 1997, the irony is that the post-handover government has not just allowed them to survive but given them more space and resources for development.

Previous Chief Executives personally chaired an annual district administration summit attended by members of all 18 district councils. District Council members were given bigger monthly allowances plus subsidies for the setting up of district offices, similar to those for legislators.

Following the passage of the political reform blueprint spearheaded by Donald Tsang, five “super-district council” seats were set aside for district council members in the 2012 Legislative Council.

In his maiden policy address in January 2013, the then chief executive Leung Chun-ying announced a one-off grant of HK$100 million each for all 18 district councils to improve their neighbourhoods.

Thanks to abundant resources, the pro-Beijing force had succeeded in winning the hearts and votes, in whichever order, of voters in district councils through neighbourhood services and handouts like dumplings and mooncakes and snake and vegetarian banquets.

The story of the phenomenal success of the pro-Beijing camp in district elections came to a shocking and embarrassing end in the 2019 district council elections when they suffered a humiliating defeat amid the anti-extradition public outcry.

A veteran leader of Federation of Trade Unions, Alice Mak Mei-kuen, who lost her district council seat, reportedly bursted out her anger with a four-letter word starting with “ f ” when she confronted chief executive Carrie Lam face-to-face. Mak blamed Lam for their election shame.

Mak, now the minister in charge of home and youth affairs, is spearheading the promotion of the district council revamp package that, if passed, means fewer seats open for her ex-colleagues to regain their pride after the miserable defeat in 2019.

Adding more irony is that the FTU and the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment of Hong Kong and the whole pro-establishment camp are all out to canvas public signatures in support of a government package that drastically reduces the number of seats up for grabs through election.

Taking no chance of democratic elections, Beijing woke up to the British plot that was launched with a bang in 1982 with a system revamp and a confession.

Speaking of the revamp, Chief Executive John Lee told reporters “(We) had gone down the wrong path (in the past),” adding the Government was putting district councils back on the right track.

Where the path will lead to is anybody’s guess. But the new structure looks like a strange creature, being part of the executive authorities but with a fraction of its members being chosen by the people, to whom they are supposed to be accountable.

In his regular column published on Chinese-language Ming Pao on May 8, former housing minister and academic Anthony Cheung Bing-leung said district councils must not be ossified to be seen as an executive tool or a subordinate of the Government in district administration regardless of the form of their revamp.

Elected seats should be simply abolished if the will of officials prevails everything following the revamp, he added.

That could not be a more ironic throwback to the pre-1982 colonial days. What a 41 years!

▌[At Large] About the Author

Chris Yeung is a veteran journalist, a founder and chief writer of the now-disbanded CitizenNews; he now runs a daily news commentary channel on Youtube. He had formerly worked with the South China Morning Post and the Hong Kong Economic Journal.